DENNIS PETER LIDDINGTON

by Alan Ram

The Tax Officer�s Fate

1. Dennis Peter Liddington�s pretty pickle, and what led up to it.

I have Dennis Peter Liddington at my mercy. He�s standing on his tip toes in the middle of the room. I�ve had him like that for the best part of two hours, in fear of his life, with terror in his eyes. I could run him through with the knife in my hand, with the long-bladed kitchen knife. Watch out, Dennis Peter.

His legs are aching. They�re beginning to cramp up something terrible. He�s pleading with me and making little gestures like he�s desperate to sit down and rest his legs.

And I taunt him. I say What are you after, Dennis, a chair, an armchair, a settee? How about a double bed with a duvet?

And then he wants water. He�s rocking about in front of me and he starts to open and close his mouth like a fish, and he�s crying out loud - Oh, what have I done to deserve this? I�m under extreme stress, my heart could give out at any time. Do you want the death of a man on your conscience? At least a glass of water. For charity. For the love of God.

And I go walk right up to him and I say Christ, man, how can I put this so you get it through your noddle? You can die of thirst for me. You can whistle for water. I wouldn�t piss on you.

Dennis, you�ve no idea how I�ve suffered because of you.

Dennis, you need to feel my pain.

I�d like to rip open my belly with my bare hands, exposing my internal organs, and grab hold of you by your hair, and stick your face in the mess. I�d like to stick your face in the remnants of my guts. There, Dennis, drown in my juices and see how you like it.

Oh, you�d be saying. I can�t breathe, my breath won�t come my lungs are filled with internal juices, secretions of blood and bile. What a way to go. Jesus, Mary, Mother of God if I could just have a few more minutes on this earth. I haven�t finished. I have things on my conscience still, people I�ve not made it right with. Places I haven�t been, Bali, Thailand, I�ve always fancied Bangkok..

No, Dennis, I�d say. You can plead all you like. I�m unmoved.

I ask Dennis a question. Where are my wife and children?

He looks at me perplexed. What? How should I know?

Children, Dennis. Wife, Dennis. I have a wife and children. You have a wife and children. Yours are at home. Where are mine? Are they here in this room? No, they�re not. Are they in this town? No, they aren�t. This country? No, by no means. We�ve been torn asunder! If I want to look at my lovely wife and my gorgeous children, I have to take out a photograph.

My wife, Dee, I tell him, Short for Diana, and my children, Toby and Lucy, are in South Africa. Which is a hell of a long way away how ever you look at it. I�m here and they�re there. Oh, and how did that come about? Here I am, a man of forty, a white male in his prime or close to his prime, and my near and dear are out of reach on the other side of the world. Plus all I have to my name to call my own are the clothes I�m standing up in. How did that come about?

And Dennis is thinking to himself: he must be exaggerating for effect.

I am not exaggerating in the least. My house was stripped bare, Dennis. A plague of locusts couldn�t have done better. I came home and there wasn�t a stick left. I walked in the door to find a house empty of contents, a wife who�d gone out of her head, unable to speak at all, and my children walking up and down the stairs and in and in and out of the back door, crying their eyes out both of them.

Picture the scene earlier that afternoon, Dennis, if you can. Toby, eleven, walks through the door, takes one step into the house and stands transfixed with shock, his mouth gaping open, not able to take in what his eyes are telling him. Then, a couple of minutes later a rerun with his sister, Lucy, nine.

They look at each other.

What�s gone on here? What to do?

Lucy snaps out of it. She takes walk along the hall and into the sitting room. And there in the middle of the floor is her mother, sitting like Buddha or someone, staring into space and rocking gently to and fro.

- Mother, what�s happened? No reply - Mother what�s the matter with you? Not a word.

Denis, she was a week in hospital with head doctors tiptoeing around her before she uttered a syllable.

Is it surprising? Not at all. Her life was turned on its head in a moment. I�ve given her a kiss and a wave goodbye, and she�s eating a bit of toast and drinking her coffee. And she takes bite of her toast, and before she�s finished masticating there are four burly men loading the contents of her home into a large truck. Heave ho, they�ve done this before. The beds are down the stairs and out the front door without touching the sides, in a blink, with them whistling and humming as they go about their work.

- What are we supposed to sleep on?

- Not our problem.

- Lucy�s computer. Oh no! What harm has she done you?

Our house is invaded and stripped bare by locusts, locusts in human form, before her eyes. And it�s too much for her poor head to take. And she slips to the floor and lapses into silence sitting on the bare boards, staring off into space. And it is in this pitiful condition that her children happen upon her, and from which she has slowly to be nursed back to full health, if ever, I hope, it�s in the hands of God.

Not to speak of the damage done -- I�m talking long-term damage -- to the psyches of young Toby and Lucy. Unknowable, but certainly not slight.

Dee was taken off to hospital in an ambulance, and it was a week before she said so much as a syllable, and three weeks before she was discharged, supposedly into the care of a female friend. Why not my care, Denis? She blamed me for her suffering and loss, that�s why.

She stayed one night with her female friend and the off she went without notice, without warning. Without my agreement she flew to South Africa, taking Toby and Lucy with her.

Why South Africa? That�s where she grew up. That�s where her parents are.

She was on the phone to her mother from the hospital once she got back the power of speech, and poured out the whole story with sobs and silences.

- I can�t believe it, says her mother. Oh, you poor thing.

- What is it? Her father wants to know. - What�s happened?

- It�s Dee. She�s homeless and penniless and she�s been in hospital for her head in England for several weeks.

- Tell her to get on a plane.

- She doesn�t have the money.

- I�ll buy the tickets from this end.

And off they went. And that is where they are now, Dee and both my children, in the bosom of her parents.

And what contact do I have with them? None, practically. Oh, you�re thinking, what�s wrong with the telephone? Why doesn�t he give them a ring and stay in touch that way? Of course I telephone, Dennis. But the disembodied voices of my children every now and then, how much do you think that�s worth? And a wife who won�t even come to the phone to exchange the time of day.

My emails go unanswered:

My darling Dee, my only love, and wife of so many years, mother of my children, you have no idea how terrible and wracked with guilt I feel after what has gone on and what you have had to endure. What you have had to put up with no wife should. What a terrible time it has been for you, my darling. I can only hope that the sun and daily exercise and the company of your parents in the familiar surroundings of your childhood will act as a comfort and bring you to yourself, and that we will speak before long. Love and kisses, and give the children a big hug from me.

It�s not satisfactory, Dennis, surely you can see that. Try to empathize.

I�m cut off from those I love. I�m on my uppers, materially speaking. I spend my evenings in this little rented flat. No wife. No children. No house. No business.

It�s amazing how quickly life can swing from one extreme to the other. What a merry go round it is. One month you�re awash with money. The phone is ringing hot with business. You�ve money coming out your ears practically, you�re carrying it home by the wheelbarrow load.

Then, before you can count to ten, your best customer�s gone belly up. Thirty grand down the shoot. Thirty grand, Dennis. Where do you go from that kind of kicking? Down Dennis, that�s where. You�ve got money haemorrhaging out your arse and fuck all coming in. Your days are filled with ugly conversations. I�ll give you an example:

I�m on the phone to this bloke. - I want my money, he says.

- If you can wait a while.

- Bollocks wait a while. I�ve waited four fucking months, you cunt. I�m in the wood flooring business. I�m not a fucking charity. Nineteen thousand four hundred and eighteen pounds. I want a cheque. If I don�t get a cheque today I�ll fucking hammer your head. I�ll send a crew round to do you, you cunt.

Finally, I was wallowing in self-pity, I don�t mind admitting it. Oh, woe is me, the earth is slipping from under my feet, I thought to myself.

But I always kept a brave face on to Dee and the children.

Did I receive your letters, Dennis? Yes, I�m sure I did. But the bills were piling high and unopened at the time.

You sent your first letter, Dennis. You waited. No reply. You sent another. Still no reply. And another. The same thing.

And at some stage you thought to yourself, Right, I�ve had enough of this. Who does this bloke think he is? I�ll show him what�s what.

You composed a final warning:

�Dear Sir,

I�ve sent you letters. Not one letter, or two, but many. How many I�ve lost count. And I�m sitting here at my desk waiting for you to favour me with a reply, and I�ve had it up to here, you�ve tried my patience just a bit too far, and now you�re going to get what�s coming to you and I�m going to enjoy dishing it out�..

Dear Sir, on the basis of information provided from here and there, and following our investigations, following comprehensive investigations of your chaotic financial affairs, I�m able to tell you, I�m happy to tell you, I�m writing to inform you that if you don�t remit the sum of, a very large sum, add a zero, add another zero, why not, if you don�t remit the sum by the date specified in settlement of your outstanding tax liability, you�ll be taken to the cleaners metaphorically speaking, all assets, house, contents of same, car, anything worth taking and selling that you have anywhere that we can lay our hands on, any money you might have squirreled away in bank accounts or under mattresses or in metal boxes in holes you�ve dug and then filled in with the intention of returning later, etc, plus wife, plus children it goes without saying, everything in fact except sufficient clothes to keep you decent will become the property of her majesty�s government of which I am proud to be the agent, operating in a humble if you like but vital capacity.

REMEMBER, THE CLOCK IS TICKING�. UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES IGNORE THIS COMMUNICATION WHICH HAS BEEN SENT BY RECORDED DELIVERY.

Thanking you for the favour of a prompt response.

Yours faithfully,

Denis Peter Liddington.�

And Dennis is so proud of his composition he shows it round the office.

- What do you think? Will this go down well?

- I�d give a few pounds of my own money to be there when he opens it.

- I hope he doesn�t have a weak heart.

- I hope he has a paramedic team standing by on full alert.

- I hope his life insurance is adequate.

- This�ll settle his hash. It wouldn�t surprise me if he went and bought a gun and shot himself.

- I wouldn�t be surprised if he took pills, if he slashed his wrists, if he threw himself off a high cliff, off a bridge, if he put the whole family in the car and fed carbon monoxide into the vehicle via a tube from the exhaust in the confined space of the garage.

I have explained to Dennis Liddington how I came to be reduced to my present state of emotional and physical isolation and material penury. And through the pain of his cramping up legs, plus his well-justified fear for his own life, he hears me.

But does he have any sympathy at all? No. Is there a trace of humility? There is not.

What is he thinking? He�s thinking: Well, if he�d only asked my advice he wouldn�t have found himself up the creek in the first place. If he�d only been a little more circumspect and thought ahead he�d have been fine and well able to settle his outstanding liability to the revenue. It wouldn�t have been a problem. What he should have done was bought a pot pig and put a little money away in it each week when times were good.

And I turn on him in a rage and I say Pot pigs! What the fuck are you talking about pot pigs for. You unfeeling bastard, Dennis.

And then I add, to shame him: My hair fell out of my head, what does that tell you? I go to bed with a full head of hair and I wake up and the pillow is awash with hair, you can�t see the pillow for my hair. Lord, what�s happening? I give my head a pull and hair comes out in handfuls. I�m going bald now! My heart is pumping in my chest. Oh, no, not that, the final humiliation.

I go to the doctor. - Doctor, what the hell is going on? I have no history of baldness, premature or otherwise on either side of my family.

- Are you under stress? Asks the doctor.

- Under stress? How long can you give me?

- Eight minutes.

- It�s not long enough. I could hardly make a start.

- Probably the hair will grow back.

- Do you think so?

- I�d say there was every chance. Once you�ve been able to put your current traumas behind you.

And he was right, Dennis. When I got to plotting my revenge, my hair began to grow again. And as you can see, I now have a rich and luxuriant growth, possibly more so than before.

I did my homework, Dennis Peter Liddington. I didn�t go dashing in.

I could have done. It would have been understandable in the circumstances, with my wife out of her wits on the front room floor and my children in tears, and all means of support ripped from under me, I might have gone off pop! I might have driven across town the very next morning and confronted you directly at your desk. - Here, choose a pistol. Outside in ten minutes on the front drive and we�ll sort it out.

Don�t think I wasn�t tempted. But no, I said to myself, do the sensible thing. Follow him home. Discover his routine. Spot your window of opportunity.

I parked next to your office. Out you came with another exhausting day of paper shuffling behind you. Out the door and off home, collecting young Mark, nine, en route.

I�m on your tail. I can see your heads bobbing. That�s nice, a bit of quality time with the lad at the end of the working day.

- How was school, son?

- I got twenty out of twenty in the maths test.

- Well done. But I�m not surprised, son. With your genes I wouldn�t expect anything less. Have you thought about a career yet, son, because I think a tax officer could be the very thing you�re cut out for?

Eighteen minutes after leaving work you�re home and in your driveway and unlocking your front door, and you disappear inside with young Mark. And I think to myself, I�ll just wait here on the other side of the road and see what happens.

Twenty eight minutes later to the second, Cristina, wife and mother, comes clip clopping along the road, hot foot from the station, with her laptop in hand. Followed fourteen minutes after that by young Emma, eleven.

I follow you home each day and keep a watching brief on your house.

And every day is the same, just a minute or two either way. Except Friday. On Friday young Mark is no sooner home than he�s off out again, changed and in his cub scout uniform. Leaving you alone in the house. For how long? How long have I got? Twenty two minutes. Twenty two minutes from the boy pulling the door shut behind him and heading off to cub scouts to Cristina�s arrival.

And I check it out the next two weeks to make sure.

I have twenty minutes minimum.

Long enough. My window of opportunity.

I sat there outside your house the first evening, Dennis. There was just you and your boy inside, and I thought now, go in now, and take your revenge! My God, I was tempted. I could have overpowered the both of you, no trouble. But I said to myself, no, it�s not right, it�s the father you�re after, not the lad. If you dash in now you�ll terrify the boy out of his wits. You�ll be standing there with your knife in your hand and the boy will be screaming his head off. And you�ll be saying � No, no young Mark, you�ve nothing to fear personally. Calm down. But he�ll be screaming all the more and you�ll have to put a stop to it � In the cupboard lad. That�s it, in the cupboard, you heard me. And you end up stuffing a sock in his mouth and binding his hands to keep him quiet. You�ve taken care of the boy but then you�re haunted for ever by the terror in the his eyes.

No, no, no. I was tempted to rush your house and get it over the first night. But common sense and decent feelings prevailed.

I waited. Until the third Friday.

I let Mark leave in his cub scout uniform. Two minutes later I knock on your door. - Excuse me, sir, I�m from the police. We�re visiting households in the area checking on security arrangements. I need to take a look at your windows.

- Look at my windows? Do you have a badge I could see?

- Of course sir, a wise precaution.

And I reach in my pocket and out comes the knife. - Will this do for identification? And Dennis sees the danger he�s in, but too late. I�m over the threshold and round the other side of him and backing him out the door. - Get your hands in the air and keep them there till I tell you.

- Who are you? What is this? Take what you like, only don�t hurt me.

- Get into your car. Drive where I tell you. A single wrong move and you�ll be slashed from stem to stern.

By the time Cristina arrives home to find her home empty we�re safely tucked up here in my little flat.

Cristina gets home and she sees at once your car isn�t in the drive. And then the front door�s unlocked. The front door�s unlocked and your briefcase is in the hall. Dennis has gone out and left the door open? thinks Cristina. That�s not like him, that�s not the man I know. There�s something strange going on here. And her heart is going pit pat. I know, she thinks, try the mobile. So she does, and she�s no sooner finished dialling than she hears William Tell playing on the front room carpet. Gone out without his phone? Left his phone lying on the floor? More and more peculiar. And she�s starting to get worried now, and she goes round the house calling Dennis! Dennis! She checks everywhere. Is he under the bed? No. Is he in the bath? No. She checks the loft. She checks the garage.

- Dennis, Dennis, where are you?

Then she thinks, I know, I�ll try asking next door, maybe they saw something. But there�s no one in. And she�s standing with her finger still poised over next door�s bell wondering what to do next, when Emma, who�s arrived home and spotted her mother, appears at her side.

- Mum, what�s going on?

- Where�s your father?

- Isn�t he in the house?

- No, he isn�t.

And so on. Then down to the scout hut.

- Mark, where did your father go?

- Nowhere that I know.

- What shall we do, Mum? Says Emma.

Think clearly, says Cristina to herself, keep a grip. - We�ll give him an hour then if he�s still not back we�ll call the police.

- The police? You don�t think something bad�s happened to him?

- No. Of course not. It�s just to be on the safe side.

She�s thinking to herself, I must be strong for the sake of the children. But then Mark starts to cry, and Emma starts to cry. And before long Christina�s sobbing too, and the only thing to do is give each other a big hug, and hope for the best.

Look into my eyes, Dennis. What do you see? Sort of meek and mild English wouldn�t say boo to a goose eyes, would you say? That�s where you�re wrong.

Dennis Peter Liddington�s mind is working overtime. He�s figuring: the police will have spotted his car. They�ll have traced it to this address. Or someone will have seen him arriving here at knife point. The police will be fanning out around the building at this very moment, taking up positions, about to effect a rescue - Come out at once! You are surrounded and resistance is futile.

Forget it, Dennis. I�ve sold my car. I took a bus to your home today. And no one saw us arrive here. This flat overlooks a primary school, conveniently deserted at six o�clock in the evening.

Is Dennis worried? He should be. He should be shaking in his shoes.

But he�s not wearing any shoes.

Is he not? Then he should be shaking in his boots.

But he�s not wearing any boots.

Is he not?

No. He doesn�t even have socks on to cover his toes.

It�s a precaution. Dennis might hatch the idea of suddenly hurling himself through the window glass and trying to run off. But he wouldn�t get far on his naked pink feet. I�d rugby tackle him to ground and punish him with my knife.

Your best chance of escaping from the pickle you�re in might be a spot of begging, Dennis. Why don�t you try throwing yourself on my mercy.

Dennis has no previous experience of begging to draw on. He wants to know how to go about it.

- How would I know, Dennis. You�re the one with the problem. Just make something up.

- Please, please sir, let me go. Dennis croaks.

- Not bad. But lacking in emotion. Say it again, but with more feeling this time.

- Please, please let me go! And tears spring from his eyes.

- Excellent. Moving. Anything else you want to say?

- My life is worthless.

- Agreed.

- My life is worthless, but think of my children. Take pity on them. They need a father.

- Stop, stop! You had a chance, Dennis. I gave you a last opportunity to save yourself, but you�ve blown it right out of the water. There is no way I�ll spare the life of a man who stoops so low as to try to hide himself behind the skirts and trousers of his children.

I�m sorry, Dennis. Your goose is cooked.

2. A possible scenario.

Photographs are used to torment the police and Dennis Peter Liddington�s wife. After which we can imagine that Dennis was killed and the body disposed of. Buried under concrete. Dissolved in acid. Dropped out of an aeroplane over the jungle.

The first lot of photos were shocking. And he didn�t only send them to the police, which would have been bad enough. Mrs Liddington received a set too. She slit open the envelope and extracted the photos. She was confronted by images of the face of her missing husband. The face of her husband, but covered with a mass of abrasions and cuts and bruises. The mutilated face of her husband. The face of her husband with a blank, dead look in his eyes. The look of a man still alive but whose future is out of his own hands.

Synthesising the opinions of colleagues and acquaintances, we can say the following:

Dennis Peter Liddington is a decent, conscientious public servant who has never thought harm of any person or thing in more than forty years of life so far as we know. He is a keen coarse angler and is often to be seen on the edge of little lakes within striking distance of his home, sitting with his rods and other tackle beside him, trying to lure the fish. While following the blameless pursuit of fishing he always has a few pleasant words for fellow anglers or anyone he meets. Dennis in no way deserves the suffering we can imagine he is going through. And neither does his innocent wife, Cristina Liddington.

Here are three representative quotations from members of the public who are taking an interest in the case:

- Sending those photos plumbed new depths.

- We are dealing with a very sick mind here.

- The sooner he is apprehended the better.

The first set of photos were shocking. The second were worse.

A dozen images of the missing man, apparently dead, taken from various angles and distances with a digital camera and conveniently packaged onto two compact disks, one for the police, and another gratuitously and perversely sent to Cristina Liddington, though luckily intercepted by a quick-witted woman police officer noted for her empathetic qualities and who was liaising with the Liddington family and providing emotional support.

The pictures were as sharp as a tack. Dennis Liddington couldn�t have been any bolder and brighter if you�d been in the room with him yourself. His hands were tied together with wire strong enough to support his weight of seventy two kilos, and all five feet eleven and a half niches of him was suspended from a beam by his wrists, with the ends of his toes just barely scraping the ground.

The two policeman who first viewed the pictures had no difficulty in imagining his pain.

- That wire must have cut into his wrists something terrible.

- His leg muscles will have cramped up.

- You can see from his face, he went through agony.

- We can only hope he wasn�t trussed up like that for long.

- I�ll second that.

Later, over a pint of lager, the same two policemen discuss the case further.

- The man responsible for this outrage�.

- It could be a woman of course until we know differently.

- But what are the odds against it?

- Quite long.

- Very long. No, it�s a man we�re looking for here. A resourceful, determined man with a grudge against this Liddington fellow. The man owes the tax authorities an unpayably large sum of money. And he blames Liddington personally. Plus the tax demand coincides with other financial disasters in his business world.

- All of which has had terrible knock on consequences for his personal life.

- That�s it.

- Definitely a man.

- If it was a woman she would be conducting her campaign differently. She�d be sitting down outside D. P. Liddington�s place of work with a homemade sign around her neck made of cardboard and reading: HOMELESS AND DESTITUTE BY VIRTUE OF THE INLAND REVENUE. PUNISH ME NOT MY CHILDREN. And she�d have the television and the papers on the scene. It would be a carry on, but of a different kind.

3. Scenario two.

No photographs of Mr Liddington are sent to the police or Mrs Liddington. Instead, following his disappearance nothing more is heard of Dennis until two days later, when, during a search of the countryside within a three mile radius of his home, his body is discovered, by the police, hanging from a tree branch. Suicide.

His wife Cristina is distraught. But summoning all her resources she�s holding herself together for the sake of the children.

- I realise it�s distressing, but I have to ask you to identify the body of your husband.

- I understand, officer. Lead the way.

What madness entered the head of Dennis Peter Liddington, a minor tax official, and made him walk off into the woods near his home, a local beauty spot, and take his own life? Were there countervailing voices?

- Dennis, don�t do it.

- Consider your responsibilities.

If so, they went unheeded. He took himself off into the woods, a man with a wife and young children, and a house, and a pension to look forward to, the pleasures of a grandfather in due course probably, though some way down the line, and days spent fishing by a river bank with the sun winking on the water and the birds singing all around him.

The case was widely reported by the media. Dennis�s personality was trawled over.

- Was he a solitary man?

- Solitary? No, I wouldn�t say so.

- But a man who needed periods of solitude.

- That�s fair to say.

- So fishing was an ideal pastime?

- Fishing, and also walking.

- But do you think maybe he was carrying some terrible worry around with him, and it finally unhinged his brain?

- Of course. He was thinking to himself: this is no good, I can�t go on doing a job like this every day for another twenty years. It�s got to the point where I�m too ashamed to look at my face in the bathroom mirror. What point is there in a pension if I can�t live with myself in the meantime? And finally he became overwhelmed with guilt, and he cracked up and took his final walk in the woods.

- Do you think if he�d been able to talk unburden himself to someone it would have made a difference?

- Very likely.

There was a note at the scene of the suicide. A handwritten letter to his family along the lines of: By the time you read these words I will no longer be with you, I will hopefully be in a better place - who knows? - but anyway don�t take this personally, it�s just that I have had enough of who I am, professionally speaking, I can no longer look myself in the eye, and I don�t deserve to live, that�s it in a nutshell. But always remember that I love you very much. Goodbye. I remain your father, or husband, as the case may be.

He writes this note and then he tops himself. And he�s discovered dangling from a tree.

And in the middle of the funeral, during the funeral service, his wife Christina rushes out of her pew and up to coffin and hammers on the side and she shouts - Bastard, Dennis, you selfish bastard. What about me and the children? And she has to be dragged away from the coffin by her brother and father and taken outside and calmed down and given a glass of water. And the service is suspended for some minutes. Which was a scandal and an embarrassment, and the children�s eyes were out on stalks. And of course it was in the papers and on television, with photos of Dennis and Christina.

4. Scenario three.

After his disappearance nothing more is heard of or about Dennis for two days. Then his body is discovered hanging from a tree branch in a local beauty spot by a man out running with his dog. Not suicide.

Suicide?

Oh, that would be handy, wouldn�t it, Dennis. An unhappy man , but a good husband and father. A man consumed by remorse and depression, and who kept his feelings to himself. If he�d only been able to talk. If only he�d been able to unburden himself to Cristina. What a sad waste of a life.

Suicide? I don�t think so.

No, no, no.

You�re not going to get away with suicide, Dennis.

Mrs Liddington reported her husband missing on the Friday evening, about half past seven. It seemed careless of him to have gone out leaving the house unlocked and without giving his wife any indication of his whereabouts. However, the circumstances were not especially suspicious and Mrs Liddington was advised to go home and wait for her husband to turn up. Tragically that was not to be the case. His body was discovered in a beauty spot some miles from his home early on Saturday morning by a jogger.

- Mr Liddington was a family man, and I�m sure all our thoughts are with his wife and children at this time, said the police spokesperson.

Roberto Silva was jogging along the path with his dog beside him thinking is there anything finer than a run while the dew is still on the ground, it gets the day off to a good start. Then suddenly his dog shoots away into the trees, and starts barking his head off. Something peculiar here, thinks Roberto, and he follows the dog. And when he catches up with it, the animal, still barking like nothing on earth, is standing over a pair of trousers and a set of underwear and shirt all neatly folded in a little pile. And in the pockets of the trousers - Roberto didn�t go looking in the trouser pockets but the police did, - there were two rubber bands, a large clean white silk handkerchief and a small red onion, which had been pealed.

- Did your husband normally use silk handkerchiefs, Mrs Liddington?

- No. Paper tissues.

- And how about the onion? What could that have been for?

- I�ve no idea.

- The rubber bands?

- Sorry.

And five yards away from the clothes was Dennis�s body, swinging from a tree branch, with a rope around its neck, dead. Which gave Roberto Silva a hell of a start. And near the body was a little wooden stool lying on its side.

Hearing the story so far Dennis�s friends and family, and the generous minded, leap to his defence.

- It could still be suicide. He was a man in extremis. He was thinking to himself: I came naked into the world and naked I�m going out, and at a moment of my own choosing. Forgive me, mother.

You�re on the wrong track. The body was not naked.

- Naked except for a pair of shoes?

No.

Mr Silva took some calming down before the police could get a statement from him. - Take a swill of your tea and few deep breaths, Mr Silva, and in your own time describe what you saw. Was there fruit involved? Oranges or grapes or mangos, to name three?

- No.

- Or vegetables? The deceased�s nostrils weren�t blocked with small carrots for example?

- No.

Dennis had on a pair of good brown brogues he wore for walking, and a pair of socks, and he was dangling several inches off the ground, too far above the ground, unfortunately, to save himself. He was dressed in a pair of his wife�s panties, frilly edged lace panties, or at any rate panties with the appearance of lace. The panties looked an uncomfortable long-term proposition on a man, but stimulating in the short term. His organ was poking through a hole slashed in the front with a Stanley knife. And his hands were loosely secured in front of him with layers of gaffer tape.

What we have here, the police concluded, is an autoerotic episode that went tragically wrong.

You�re standing on a little stool you�ve brought with you, Dennis, dressed as I�ve described and with a rope around your neck attached to a convenient branch. You have a little listen to check you�re on your own. All you can hear is birdsong. And what you do then is you swing away from the stool in a controlled fashion, you go back and forth, and back and forth, and so on. And you�re thinking to yourself lovely, lovely, this feels lovely. Your whole body is overwhelmed by an exquisite feeling. But then, in your excitement, unfortunately, whoops, you forget yourself, and you give the stool a bit of a kick with your foot, accidentally, and over it goes and rolls away. Whoops a daisy.

An unfortunate accident. One minute Dennis is swinging ever so gently backwards and forwards, from the stool and back to the stool, gripping a Stanley knife firmly in his right hand � Oh yes, yes, please. He whimpers. � Yes, yes please, more of this. His plan is, after the moment of fulfilment, after a few seconds when he�s restored to himself, he�ll liberate his hands with deft little cuts or slashes of his blade, and take the rope from around his neck, and dress himself again in his own clothes, and that�s it, Bob�s your uncle. � Good. I feel better for that, he�ll say to himself.

But it doesn�t work out. One minute he has the motion perfectly under control. And then before he knows it the stool�s gone missing, and the knife�s on the ground, and Dennis is dangling and choking, choking and dangling and twitching about.

His last words to his wife, the last words his wife remembers him saying are - I�ll be back for supper, dear. Shouted over his shoulder as he put his rods and tackle and nets in the boot of his car. As we now know the rods and tackle were a ruse or blind only. Mr Liddington numbered fishing among his hobbies, but he had no fishing planned on this occasion. He put rods and tackle in the boot of his car, where they joined presumably also other items, viz. rope. viz. little stool for standing on. viz. gaffer tape. viz. Stanley knife, viz. items of female clothing, and what not.

- I�ll be back for supper, dear, he shouted. But in fact, by supper time he was dead. His body was found by the jogger already named and in the manner described. And his car was recovered from a car park on the edge of the park, with his fishing equipment still in the boot, and showing no signs of having been recently used.

All in all, to sum up, the cover Dennis had arranged for his autoerotic hanky panky was blown out of the water.

Dennis was revealed for what he was.

5. Dennis�s autoerotic-episode-gone-wrong is witnessed by his tormentor, who then flies to South Africa to pick up the pieces of his life.

You�re hanging by the neck, with your feet tantalizingly close to the ground, and with the bony fingers of your bound hands clutching and pulling at the rope but to no good effect, and you�re writhing and kicking out frantically.

If you keep kicking like that, Dennis, you�re only hastening your end. It�s up to you.

Not much longer to go now, Dennis. Courage, mon brave. Hang on in there.

I feel in my jacket pocket for my passport and my ticket. Both present and correct.

I�m tempted to stay until its over and you�re good and dead. But no, I have somewhere to be.

I leave you.

And your body hangs there all night in the woods, Dennis. All night, and through the glimmerings of dawn and birdsong, with rigor mortis setting in. All night and into the next morning, until Roberto�s dog sniffs you out.

Meanwhile, Dennis, I�m on a plane in the sky over Africa, headed south with only hand luggage. A couple of shirts and changes of underwear, three pairs of socks, a wash bag, and two family photos in frames.

And I may be breathing recycled air, but it tastes sweet to me. It�s the closest to fresh air I�ve breathed in quite a while.

South Africa here I come. I�m coming, my darlings, your daddy will soon be with you. A few weeks of sun on my back and frolicking in the pool with the kiddies, and lying by the poolside with a panama hat on my head and a beer in my hand. - Another beer?- I don�t mind if I do. A few weeks of that, and I�ll be more myself, Dennis.

� Alan Ram

Reproduced with permission

HABLE CON ELLA

HABLE CON ELLA  HAPPINESS

HAPPINESS AMORES PERROS

AMORES PERROS CIDADE DE DEUS

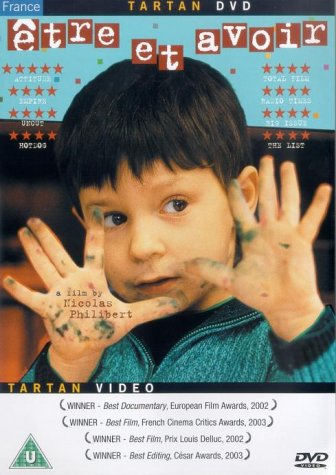

CIDADE DE DEUS ETRE

ET AVOIR

ETRE

ET AVOIR