Guranov watched Zemlinsky as he slowly - oh so slowly - pushed his barrow down

the slope. He moved at snail�s pace. A woman would be quicker. A small child

would be quicker! When he finally reached the bottom, Yartsev, stood at the

spoil heap, filled the barrow with waste. Zemlinsky then began the ascent. But

he was even slower coming uphill. He plodded along with all the zest of an

arthritic cow. He would slip every few steps and have to painstakingly cover the

same ground again. When he eventually reached the top Guranov helped him empty

the barrow onto the wagon and the whole tedious process started again. They

would miss their target again today.

If only Guranov, or Yartsev, could get on the barrow it would be so much

quicker. But prisoners were not allowed to arrange their own working methods.

The guards had placed them like this so they had to continue like this. If only

they had two barrows. But barrows were rationed - one per team. Here they were

in Siberia, on the edge of one of the biggest forests on the planet and simple

wooden barrows were rationed. Two carpenters and a band saw could easily turn

out a hundred barrows a week here. Instead, all barrows had to be requisitioned

and sent from Seimchan, over five hundred kilometres away.

�We have the allotted number of barrows for this site, Seimchan will not send us

any more� Guranov had been told when he complained of a shortage to Putin, the

camp�s sub-commandant. Guranov politely explained that it would be easy to make

their own barrows, they would not have to get them from Seimchan. �The plan

contains no provision for us to make our own barrows.� When he pointed out that

making their own barrows would aid speedy completion of the plan Guranov heard:

�Yes, of course it would, but the plan contains no provision for us to make our

own barrows.�

�Then can�t we change the plan?� suggested Guranov helpfully.

The sub-commandant managed to look appalled, incredulous and alarmed all at

once. �The plan contains no provisions for changing the plan.�

So that was that. The job proceeded slowly, unsynchronised and lopsidedly

because the plan was the plan was the plan and it must be obeyed.

Not that Guranov was particularly bothered whether the plan was fulfilled or

not. The �patriotic duty of all prisoners to ensure the success of the plan� did

not motivate him anymore - he had stopped believing in all that crap after a

couple of weeks in the gulag. No, it was his personal duty to his belly that

drove him now. Food had to be earned, and only those gangs who fulfilled their

day�s work quota got full rations. If you didn�t reach your target it was half

rations. Full rations were scanty enough, half rations barely staved off

starvation.

Guranov, like all the other camp inmates, thought about food constantly. Would

his slice of bread be a little thicker tonight? Would he get his stew from the

bottom of the vat where it was a little richer and you may even get a lump of

meat in with your vegetables? Would he, oh please god let it be so, be one of

the lucky ones who got selected by the guards to receive a second helping? Fat

chance of that with Zemlinsky on his team. Second helpings went to the top

performing gangs, or those with something desirable with which to bribe the

guards.

Zemlinsky made the gangs work harder. He was so weak, so slow. It meant that

everybody else on his team had to work extra to cover him. If only they could

get him off their team and get a younger man to replace him they would stand a

much better chance of earning full rations. Perhaps they could get Schneider

from the toilet detail. Schneider was German but Guranov didn�t even care about

that anymore. He was a tall, strong man, wasted emptying slop buckets and

digging latrines. Yes, with Schneider on the team they could easily hit their

targets. Full rations every day!

It was that night, marching in rank back from the work site to the camp that

Guranov finally came to realise the answer to his problems. A dark thought that

had been bobbing about his unconsciousness for some time finally surfaced and

spread its rancid bloom - Zemlinsky must die.

If Zemlinsky had an unfortunate �accident� or simply disappeared he would have

to be replaced. Yartsev, the team leader might be able to do a deal and get

Schneider on the team. Or if not Schneider maybe Izmailov from the construction

gang. Anyone but Zemlinsky!

Zemlinsky was fading, that much was clear to everyone. The rheumy eyes, the

wheezing breath, the pallid saggy skin, all signs of a man on the slide. He was

old, easily over fifty, one more winter would probably finish him off. All

Guranov would be doing was giving time a helping hand. Yes, the more he looked

at the issue - logically, dispassionately - the more it made sense - Zemlinsky

must die.

Zemlinsky was a loner, he didn�t belong. There were a few other Poles in the

camp but they were in the politicals section and rarely had a chance to mix with

the ordinary prisoners. His Russian was rudimentary at best so he couldn�t

really join in conversations. He was an optician by trade, the only one in the

camp, so he had no comrades there. All in all he was isolated, alone. No one

would stick up for him. No one would miss him. The inquiry, if they even

bothered with one, would be brief and perfunctory. �Killed by person or persons

unknown� was the usual verdict when a prisoner was murdered.

That night Guranov formulated a plan. He would throttle the old man, that would

be easiest. He had a piece of rope he used as a belt that he could use to do the

deed. He�d need to get Zemlinsky alone. The fence post store - that was fairly

isolated. He�d get him to go there with him and then put him out of his misery.

If he was lucky, thought Guranov, he might even be able to scam Zemlinsky�s

rations for a couple of days. Sometimes it took the camps� administrators a

while to communicate to the kitchen that an inmate had died. Guranov would say

that he was collecting Zemlinsky�s rations for him, that the old man was too

tired to come into the mess hall himself. Double rations! Guranov might even be

able to save a piece of bread to nibble at night. He began to salivate just

thinking about it.

The next day, as the guards were changing shifts, Guranov approached Zemlinsky.

�We have to fetch fence posts for Yartsev� he said.

�Me?� shrugged the Pole.

�Yes. Come on.� Guranov led the old man into the forest. The atmosphere amongst

the trees was still and quiet, almost churchlike. The knowledge of what he was

about to do weighed heavily upon Guranov and every step he took was an effort.

To his agitated mind everything seemed exaggerated. The soft crunch of his boots

on the forest floor was loud and discordant. The forest seemed dark and dense,

the occasional patches of autumn sunlight bright and harsh. Guranov felt as if

he was walking through an over exposed photograph. His stomach churned and his

bowels felt loose, but the Russian was nothing if not determined. It was too

late to back out now, everything was in place. The plan was the plan was the

plan and it must be executed.

Reaching the pile of posts Guranov motioned to Zemlinsky to bend down and lift

them. As he did so Guranov retrieved the cord from his pocket and lent over the

smaller man�s bent figure. Sensing a shape over him Zemlinsky jerked upright. As

he did so Guranov pulled the cord tight around his neck.

As soon as he realised what was happening the old man struggled for all he was

worth. He pounded his right heel into Guranov�s right shin. Guranov flinched but

did not loosen the stifling pressure on the cord. Zemlinsky�s hands slapped the

Russians head and pulled at his hair. The assailant held on. Everything seemed

ultra real to Guranov, every sensation felt magnified a hundred times - the

slickness of the victim�s greasy hair rubbing on his chin; the coarseness of

his stubble scratching at Guranov�s knuckles; the rattling noise of his half

strangulated breathing. Zemlinsky�s eyes began to bulge horribly and spittle

leaked from the corners of his mouth. Surely it wouldn�t be much longer thought

Guranov.

Working on instinct rather than reason, Zemlinsky managed one last counter

attack. He formed his right hand into a fist, leaving his index finger sticking

out. Then, with his last remaining strength he threw that fist over his

shoulder. His long, ragged finger nail dug into Guranov�s eye.

Zemlinsky felt the moisture of his attacker�s eyeball staining his finger tip.

The Russian instinctively reached to remove the foreign object in his eye. In

doing so he released the cord and Zemlinsky was able to twist away from the

bigger man�s grip.

For a long beat the two men stood facing each other, Guranov squinting from his

injured eye, Zemlinsky battered and breathless, his neck an angry red sash.

Then, as if at some silent signal the two lunged at one another. They wrestled

and grappled in a grim death-waltz. Guranov was stronger and younger, it was

hopeless for Zemlinsky. The Russian threw him onto the log pile where his ribs

took a battering from the unforgiving wood. He kicked fiercely at his frail

legs, explosions of pain causing the Pole to cry out. Zemlinsky attempted to run

for it but stumbled and fell in an uncoordinated heap.

Guranov advanced on the prone man, the rope stretched between his fists, ready

to finish the job. The brutalised Pole held up his hand, signalling Guranov to

stop. Sceptical, yet curious, the Russian stayed his advanced. Zemlinksy pulled

open his tatty jacket and tugged at the inner lining. What trick was this

thought Guranov. Did the lazy rat have a weapon concealed in there? He moved

menacingly towards his victim again. Zemlinsky again made furious hand signals

urging him to wait. Something in Zemlinsky�s desperate manner convinced Guranov

he was genuine, that this was no con. The stitching of the jacket lining finally

gave way and Zemlinsky fished around inside. He retrieved an object and threw it

onto the floor at Guranov�s feet. It�s burnished surface reflected the pale

autumn sunlight. Picking it up Guranov saw that it was a silver cigarette case.

It felt heavy for it�s size. Guranov turned it over in his hands, admiring it�s

smooth, flawless exterior. He was no expert but it was clear that this was a

quality object, probably worth a good deal. He opened it up. The lid lifted with

a satisfyingly smooth motion. Inside there was a fixed mirror. The base of the

tin was golden (maybe even gold?), with a star of David inscribed on it, and

several hallmarks.

Possibilities raced through Guranov�s mind. If he could get this to the local

town, possibly through a corrupt guard, he could get a good deal of money for

it. Enough to buy extra food. Maybe even food from the free workers who came to

the camp. Real food! Smoked fish, sausage, pork - not the mushed up, rotting

vegetables that passed as nourishment in the gulag. Or perhaps he could swap it

for a permanent bed in the hospital wing. He wouldn�t have to work then, and the

rations were better if you were �sick�.

A noise interrupted Guranov�s meditations. Zemlinsky had coughed. The Pole was

still lying on the ground, wretched and beaten. He motioned for Guranov to take

the cigarette tin. �For you,� he said in his pidgin Russian, �Leave me alone.�

So that was the deal. Guranov looked at the pathetic figure before him. It

crossed his mind to finish off the Pole AND keep the cigarette tin, but no, that

seemed a step too far. It would be an insult to kill the man who had just given

him this life line. Besides, Zemlinsky wasn�t that bad. True he was old and

useless, but that was hardly his fault was it? Ten years in the gulag was tough

on a man, many didn�t last that long. Zemlinsky must have been resilient or

cunning to have made it this far. Guranov slipped the case into his trouser

pocket and offered Zemlinsky his hand. The injured man declined, backing away

nervously. Come on, Guranov, indicated with a nod of his head, it�s Ok. Warily,

Zemlinsky took the proffered hand. Guranov pulled the older man to his feet and

slapped him heartily on the back, suddenly sympathetic to his injuries,

respectful of the fight he had put up.

They turned and made their way back through the dank forest to the light,

windswept work site. Zemlinsky shuffled along, his battered legs slowing him.

Guranov strode on ahead, a jaunty spring in his step, the cigarette case nestled

snugly next to his thigh.

DOGHOUSE ROSES by Steve Earle

DOGHOUSE ROSES by Steve Earle MINORITY REPORT: Volume Four Of The Collected Stories Of Philip K Dick

MINORITY REPORT: Volume Four Of The Collected Stories Of Philip K Dick SOME RAIN MUST FALL by Michel Faber

SOME RAIN MUST FALL by Michel Faber NOW THAT YOU'RE BACK By A.L. Kennedy

NOW THAT YOU'RE BACK By A.L. Kennedy NAIL By Laura Hird

NAIL By Laura Hird MIKE ATHERTON

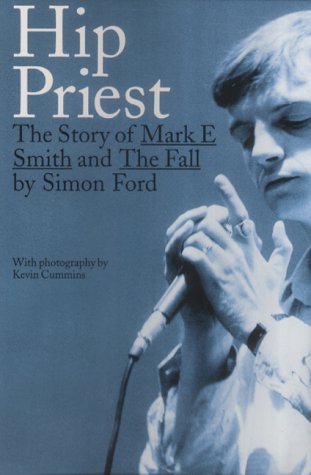

MIKE ATHERTON MARK E SMITH

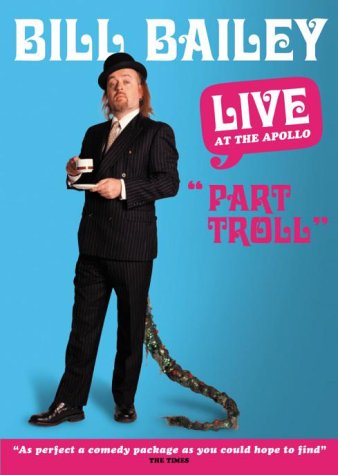

MARK E SMITH BILL BAILEY

BILL BAILEY