Shallow, not-quite-light seeps into my room; the day begins. I blink, yawn and stretch. Betty would call me �Tiddles� when she saw my morning stretches. I could never sleep through the night from the age of forty onwards. Up with the larks, I would potter in the early hours then cat-nap throughout the day. B would complain bitterly but she was always grateful for the hot cup of English Breakfast and buttered crumpet that I brought her.

The day is young; I am not. I am ninety-five today. My birthday falls on the summer solstice. The longest day of the year. As a child I saw the celebrations as in honour of my birthday. My family, being traditional country gentry, tolerated the locals building bonfires in the grounds. They even provided refreshments and joined in with the dancing. I barely remember of course because all this ceased during the Great War and was never reinstated. Only fleeting memories of the colours, smells and sheer joy remain, returning to me occasionally in my dreams.

A distant scream disturbs me from my reverie. Footsteps thud on the floor above, a bell buzzes somewhere, the day is beginning for the other residents. Perhaps their days never end or begin but simply meld into each other in an endless circus of sleeping, eating and changing nappies. As my father used to say, shoot me before I fall into that state. I�m sure it will not be long now.

Bones cracking, I ease myself up in my seat. I grapple with the controls, my fingers stiff, and finally hit the correct button to lever the chair into a reasonably upright position. I press the clockwise arrow and begin to slowly revolve so that I am facing the window. I am ready for the sun. The grey slanting half-light recedes, to be replaced by streaks of golden pleasure. I salute the sun with my hand, a girl-guide gesture that I learned in 1923 and used professionally until I retired from guiding nineteen years ago, following a scandal that I�d rather not mention.

I no longer salute the sun from the floor. Although I probably still could do the movement, I am not quite sure that I could make it back up again. B and I visited an Ashram in the sixties, when all of those things were exciting and new. We both learned yoga but Betty was always lazier than I and she did not continue with it.

I distinctly remember the last time I practised that movement. It was during my first week or so here in this establishment. They were checking on me every hour back then, as if they thought that I would try to escape or commit some destructive act on the furniture. I had been �yoging� � as B used to call it � during the intervals between their little visits up until then, but somehow had timed it wrong that morning. As I reached the apex of the movement, there was a scuffle at the door and a shriek. �Oh my god she�s fallen!� Suddenly, I was being man-handled from all directions by several young, uniformed women.

�Unhand me!� I shouted, �I�m fine.� I attempted to get up unaided but what with fighting them off and confusion with my slippers, I did fall. So I played the part then of the frail old lady and allowed myself to be carried to a chair and given hot, sweet tea. Following that fall I have not attempted any yoga. I exercise my mind instead.

I take a sip of water. My small clip-on table is crowded with paraphernalia: the jug of cranberry that is far too acidic at this time in the morning, balsam tissues, playing cards, sweet wrappers, the silver-framed photograph of Betty with the Triumph. She did look rather stunning in the leather flying-jacket, her hair streaming behind her as she sat bolt upright in the sidecar. My darling girl. I miss her so, especially in the mornings.

She was lucky to die quickly and quietly. Nothing lingering and messy, no gradual loss of the marbles or slow deterioration of tissues. It was terribly upsetting of course but not unexpected. After all, everyone dies. �Take care of yourself,� she had said to me that last morning. I tried, but we both knew that I wouldn�t last long alone. Oh, I bumbled about for a few years, burning toast and flooding the kitchen, resisting the inevitable. We had a small group of friends but they began popping off too, one by one.

I stayed in a grand hotel by the sea for a year or so, until there was a misunderstanding with one of the chambermaids. She was foreign and I believe that she thought that I was a man, heaven forbid. After that, coupled with my failing sight and a near fall in the park, I admitted to myself that I needed a minor amount of care. At least I had the backing of the investments; I had already sold the estate. Betty and I had been living in a small townhouse. Imagine my simultaneous joy and dismay when I discovered that the old family seat had been converted into a home for the elderly.

They do not allow me free board of course but they have given me a good room. Number ten, like the PM. The staff are fond of boasting that they have the crazy old aunt locked in the attic and some of them refer to me as �The Duchess�. I manage to provide the funds for this place without eating into my capital. I could keep on going for another ninety-five years but lately I feel that I just do not have the energy or inclination.

Still, the morning sun brings cheer. I smile at simple things, like the robin that sits on my windowsill or the branches of the old oak swaying in the breeze. I cannot see much further than this but I believe that the grounds are rather pleasant. They have sold off most of the land of course, to make way for �new development�, and much of the garden has been landscaped. However, I am aware of my position in the house. If my memory serves me correctly, that old oak is hollow; it is the one that I would climb and hide inside when my father went into one of his rages.

My eyes are tired. I may rest them for a moment.

�Miss Harding.� A light knock at my door accompanies the tuneful voice. �Miss Harding, cup of tea?�

I creak my neck and blink. �Yes,� I croak, cough and call louder, �Yes please!� I take a sip of water and pick up my clock as the door opens. I can see the number; I think it may be six. I press the button.

�Six-oh-seven-a-m,� says the metallic machine voice.

�It�s five-past-six, Miss Harding,� says the young girl unnecessarily as she tidies a space on my table. �Would you like a biscuit with your tea?�

�No thank you, my dear,� I reply.

I fumble for the cup handle and she guides my hand. �There,� she says with great satisfaction, and I lift the cup to take a sip.

I sigh. �Thank you,� I say. �Thank you very much.� It�s not the best quality of course but the first cup of tea in the morning is one of those simple delights that I could not live without.

�That�s quite all right,� she says. She stands behind my chair and rests her hand on my shoulder. I smell her floral scent, masking an undercurrent of sweat. �It�s a lovely morning.�

�Indeed it is,� I reply. �Today is the longest day of the year.�

�Yes,� she says and laughs. �And I�m going to sleep through most of it!�

�What a shame. Do you finish soon?�

�About an hour.� There is a movement; I think she has looked at her watch. She waits for me to drain the cup and then takes it. I�m reluctant to let her go as she seems so sweet.

�You�re new, aren�t you?� I say.

�Yes, I started this week.�

�What�s your name, dear?�

�Liz,� she says and pauses. I hear a rustle. �Well, I�d better get moving or I�ll be in trouble.�

�Short for Elizabeth!� I call as she is on her way out. I hear the chink of crockery on the trolley as she deposits my cup and saucer, then another voice before my door has completed its slow journey to a shut position.

�You don�t want to be getting over-familiar with her, if you know what I mean.�

�What?� A prickling sensation tells me that their eyes are on me. I look stolidly forwards, pretending that I cannot hear. It is not that difficult to make them believe I am deaf as well as nearly blind. They assume it anyway.

�Well, haven�t you heard about her? She�s, you know, that way.�

�No! I�d never have guessed.� The door finally closes that last inch with a sigh and their voices become muffled. Presently the trolley trundles off.

�That way�. Why on earth can�t they just call me a mad old dyke and be honest about it? People are so free with their language these days, especially the youngsters, yet the staff here seem to be entrenched in euphemisms at least two generations out-of-date. I believe it must be because they spend so much time around the old folk that they forget they are living in the twenty-first century.

I ease myself gradually out of the chair and reach for my stick. It�s a good solid one that I bought for hiking years ago. I feel my way around the room and to the bathroom for my ablutions. A quick catlick on my face to freshen up; my clean clothes are laid out ready; my teeth are in the pot. I blink at myself in the mirror, slightly fuzzy at the edges but I recognise the shorn silver hair as my own. Once I have found my specs I am sure the image will fall into place like the fitted lid of a coffin. I have some trouble with the trouser fastener but at last I am ready to face the day and whatever it may hold.

There is a frame in the hallway that I habitually use for long distances. I hook my stick over the top and drop my bag into the net hanging from the front. That old bag is one of B�s; I resisted having a handbag for so many years. Betty would complain that I treated her like a packhorse, handing over my spectacles, wallet and anything that would not fit into my pocket. What can I say? When I was strolling I liked to be free, swinging my arms by my sides, striding out across the moor unencumbered by non-consequentials like cash and keys. Poor dear girl was rather laden down I believe. And now I know how she felt; I�m not exactly unencumbered myself at the moment.

Ah, here we are. Made it to the elevator and only slightly breathless. It�s not much larger than the old dumb waiter whose shaft was expanded to fit this monstrosity. There is a queue so I wait my turn. However, the thought of tackling that dreadful servants� staircase, which caused me nightmares as a kid, gives one pause. I do not think even the staff attempt it too often.

A tinny ping lets me know it is on its weary way back up again. I rattle the gate open and then the door. It reminds me of the old apartment in New York that B and I lived in for a time, back in the seventies. That stank of urine, too. I steady myself on the frame as the horror lurches back and forth and makes its way downwards. I feel rather seasick when we hit rock-bottom.

Out now and into what I humourlessly refer to as the lobby. My father�s beautiful oak-panelled study has been converted into the reception area and Sisters� office. A massacre of dried flowers droop unarranged in some awful kitsch pots. These surround a sofa in the alcove where we used to keep a baby grand piano. There is a piano of sorts in the corner, a small upright with use of half of the keys. I�d rather not discuss the kind of artwork, if I can call it that, which has been hung in the place of my proud ancestors� portraits.

Onwards and into the dining room, which was previously the ballroom. At least they have retained the parquet flooring. I am situated at a table with others who are capable of feeding themselves. Thank goodness I am not forced to share with those who need feeding because it is enough to put one off for life. Two old duffers, one of whom is completely mad and the other a retired academic whom, although not quite imbecilic, is nevertheless exceedingly tedious. Then there is me and a lady called Gertie who is new and very quiet. She clutches her handbag on her lap as if she thinks one of the other old dears will mug her. Mind you, the state of some of them, I wouldn�t put it past them.

Among the fifty or so residents, there are another four men who share a table quite near to us, I�m afraid to say. I hear their coughs, grunts and shambles, and their disgusting comments regarding the food or the staff, and it fair puts me off. The remainder are women who, apart from the poor dear who screams for her long-dead mother morning, noon and night, are all reasonably quiet. There are the occasional upsets such as stealing each other�s food, tipping bowls onto the floor or having minor tantrums that give the venue a somewhat nursery atmosphere, but in the main I manage to focus on my own little sphere � this table.

Having spent rather a lot of my life travelling, I am quite used to breakfasting in hotel establishments. This is not the best but then neither is it the worst. The food is varied and served reasonably warm; the staff are courteous, if a little harried; the tablecloths and napkins are changed every mealtime; the teapot is bottomless.

This morning I have requested a soft-boiled egg. I do like my eggs just so. It took B a few years to get the hang of it but when she finally did it was glorious to sit in our conservatory with the golden yolk. Occasionally I used to have bacon but lately I found it tiresome to chew so now I stick to porridge or eggs. I adamantly refuse to eat the mush they serve to some of the others. Good gracious, no! This egg, however, is slightly overdone. I don�t enjoy the meal as I would like to due to the heat in the room, the excessive noise from the rabble and the nervous tick that Gertie seems to have developed.

Two members of staff stand at the table next to me, feeding their paying customers, and talking to each other over the old folks� heads as if they weren�t there. I listen for a while as they seem to be discussing a scandal. A juicy piece of gossip; some girl is having a lesbian affair with an older woman who runs a caf� with her husband, who doesn�t know about the affair but who also has designs on the girl�s mother. I am rather stimulated by this until I realise they are actually talking about a television programme and not real people at all. How disappointing. I had imagined that the subject of this excitement might be one of the other staff. Now that would make my birthday special.

I don�t suppose I�ll have any cards today. No one left to mark the occasion and I�ve another five years to wait for the telegram from the Queen. Still, I won�t allow myself to get maudlin over it. It�s only a number after all � not important in the great scheme of things.

I leave the dining room early to stake my claim in the residents� lounge. There are three lounges but the one I prefer is my mother�s sitting room, from which I was banned as a child. I was always too clumsy for her Queen Anne furniture and fine china. This no longer being in evidence, I feel perfectly comfortable there and derive a perverse kind of joy at seeing it desecrated by faeces� stains and spilt tea. There would never have been spilt tea in my father�s day; he would have whipped the staff out of the house and down the drive.

I am partial to this room particularly because it is a reasonable walk from the dining room and thus less frequented by the lazier and more unappealing of the residents. I take some exercise and work off my breakfast as I laboriously walk the lengthy corridors that I used to run down with ease. It is a while before I reach it but, by the time I get there, I feel that I deserve the blissful relaxation of sitting down in an easy chair. A quick detour to the toilet before I allow myself this luxury; I don�t want to have to get up again any time soon.

We all prefer to keep to our exclusive seats, those of us with enough marbles and mobility to decide where we sit. Mine is near to the French windows, which have now been replaced. This is contested by one of the more bolshie gentlemen who I believe was a drill sergeant and is rather gratingly common. He seems to think that by right of possessing a shrivelled penis he is the superior party in this battle. I do not need a digging-stick to evidence my privilege; history is on my side, in this case at least.

My mother used to sit at this point in the room with her embroidery and her laudanum. I would peep through the glass as a youngster, trying to catch a glimpse of this mysterious woman referred to as �The Mistress� but never the mistress of me. I remember that after I was sent away to school, on the occasional home visit I used to enjoy waylaying the scullery maids in the rose bushes under this window. I suppose in my youthful rebellion I was daring my mother to take action, which she never did. I am not sure now whether she even noticed me at all.

Around the time of the Radclyffe Hall trial, a girl in our school was sent to an asylum for just such a tryst with a servant. She may still be there now, or for all I know she may be one of the residents here. It was all hushed up but of course we found out. After this, everyone was really rather nervous around the school and the teachers discouraged declarations of passion. It was 1928 and I was sixteen or thereabouts. I resorted to a policy of �look but do not touch�. On my next visit home I stood miserably under the window with a cigarette and a scowl. If the maids were disappointed, they did not show it. This then became my habitual spot for a smoke and years later I had a bench erected where I would take my after-dinner brandy and cigar.

All gone now, naturally. The bench, the bushes, the blossoms, the buxom beauties are all now restricted to my memory. The whole area has been turfed over. A cat sporadically visits on a hunting expedition but otherwise there is little action. On a quiet day I sit and imagine those frantic moments under the roses, recalling the taste of her lips, hot breath in my ear, whispering delights, softly yielding flesh, pricking thorns. The intensity of the memory takes my breath away. I am left panting and wanting but unfortunately quite incapable. Such is the tragedy of age.

A sharp click of heels informs me that I am no longer alone. The Drill Sergeant has arrived. I hear the irritated grinding of dentures and a brisk walk to another area in the room. He hitches his starched trousers half-an-inch up and sits stiffly in the corner to brood. Neither of us speak. A minute later, Academic Duffer appears and jovially greets Drill Sergeant.

They habitually spend their days discussing golf, politics and other manly pursuits while I sit ignored. Not that I am saying I would like to enrol in the elite club they have established here in the residents� lounge. Frankly I would willingly hack off my right arm with a Swiss Army knife in preference to involvement in the tedious and dreary daily life of Drill Sergeant and Academic Duffer. However, deference to my preference is not the reason they ignore me; it is because I am a woman. This on occasion galls one.

To top it all, Gertie appears in the doorway and hesitantly steps inside the lounge. She flicks her head around the room in bird-like fashion, looking from one to the other of us occupants. Obviously deciding that she does not want to enter after all, she hightails it out again.

Due to the interruption, I have completely lost my train of thought and cannot recapture the lusty magnificence of the particular girl I had in mind. Nor am I willing to express the joy of remembrances in company. I replace my specs from where they fell earlier. Years ago I began to wear them on a cord for just such occasions. I stare at the hazy image of the lawn, attempting to lure the hunter cat to break the monotony. After a minute I blink wearily. It is no use; even the pounding of blood in my ears will not blot out the din from the buffoons in the corner. It grates on one so. What crime did I commit in a previous existence to live out my remaining days surrounded by old farts?

Reprieve arrives in the form of the ubiquitous trundling trolley stacked with tea, coffee and biscuits. �My dear,� I say to the lovely little Asian girl who is pushing it awkwardly into the room, �I do believe you have saved my life.� She grins and shows a neat row of startlingly white teeth.

�Tea is good for you,� she says and makes to hand me a cup.

�Oh, coffee please,� I say. I had meant that the duffers might shut up if they were slurping, but I let the misunderstanding pass. �With hot milk if you have it,� I add. This is a spectacular treat of which I allow myself the indulgence perhaps once a day. I refuse the proffered biscuit but entreat her to take a few for herself as she is obviously emaciated, poor girl. She laughs and says that she�s dieting, for heaven�s sake! What will young people think of next? It amazes me that to show one�s bones through tissue-thin skin is considered attractive. Had they lived through a war, I am certain that the fashion would swing in the opposite direction. I am appalled when I see the state of the women in some of the magazines; it is enough to cause one to cancel the subscription.

Once my coffee is finished, I must be speedy if I am to make it to the toilet and back before Drill Sergeant has planted his great backside in my chair. I am up and zimmering across the hall at the first sound of wheelchairs squeaking, which heralds the beginning of the queue. Quite prepared to fight my way in with a stick, I launch myself into the cubicle and turn abruptly to bolt the door.

On first appearance, the notion of having a young gal unzipping one�s trousers and removing the pants can be quite appealing. This does not take into account the reality of these dreadful net atrocities that I wear to keep the pad in place and the fact that the staff very often leave the door wide open while �toileting� several residents simultaneously. I shudder with the shame of it; it is quite beyond thought. Shoot me, I mean it, before it gets that far.

Back in the lounge, old boyo has decided to make a dash for it. �Oh no, you don�t!� I say, with my stick out ready. But the lovely little Asian girl comes to my rescue instead. She grasps him by the elbow with a steely grip and steers him towards the door.

�Come on Mister,� she says. �You haven�t been yet.�

�But I don�t want to go!� wails Drill Sergeant, like a petulant toddler.

Academic Duffer, who is catheterised, laughs, snorts and coughs. �Go now while you still can!� he crows. The girl conducts Drill Sergeant solicitously out into the corridor and I zim over to my seat unhindered. Bones creaking, I ease back into the chair and raise my feet to the footstool. I cannot stop a sigh from escaping my lips.

Oh, the comfort of an easy chair! We had few of those, back in the old days � just my mother�s and a couple for visitors. My father had a giant leather chesterfield that exhausted half a herd of cows. For my own part I preferred a chaise longue which, while patently a seat, can be utilised as a bed if the mood takes one. Plus it has the benefit of a low back thus rendering those dreadful macassars unnecessary. I would oil my hair in my youth but then was put off somewhat at the thought of soaking up some murderously pompous toff�s oil while leaning against the macassar.

I would hold myself rather stiff and straight-backed always; one must be aware of one�s posture. Now I lounge and slump with the best of them. Nurse would never recognise me. The duffer seems to have fallen asleep. At least he is making a good impression of a snoring walrus. Drill Sergeant has not reappeared, so apart from the occasional creaks and groans of the old building stretching her structures, it is blissfully peaceful in my little corner of the world.

The house was rarely this quiet in the old days. We had parties to mark every occasion and sometimes for no occasion at all. A by-election or cricket tournament or whatever would hold no interest for me, but I did love to dress up and stride around admiring all the beautiful young things that were invariably attracted to such jollies. It was here in fact that I first met B all those years ago. She was with her husband, I remember, and I was standing by the rose bushes having a quiet smoke, trying to keep out of the way having been warned by his lordship not to cause a stink. I think he was afraid of the scandal.

Anyhow, a young weasel appeared by my shoulder and asked for a light. He had a pipe in one hand and a pretty girl in the other. Introducing himself as the assistant to whomever of wherever, but not actually telling me his name, he began to enthuse about my father.

�Isn�t the Duke simply marvellous?� he sputtered. Then he went on to repeat a decidedly unfunny tale of my father�s derring-do, the full version of which I had heard several times already from the horse�s mouth. As he spoke, I watched the girl who appeared as irritated as myself. She was rather stunning, I thought at the time, wearing a fine print dress that in the correct light was almost invisible. I cocked my eyebrow at her while the weasel was in full flow. She stifled a giggle but didn�t look away. Radiant was how she seemed to me. I realised in hindsight that she was pregnant then, but it was not obvious in her shape.

At length, he brought in the reins on his mouth and elected to introduce his wife Betty to me, and to invite me to introduce myself. I smiled at Betty and took her hand. �I am charmed to meet you,� I said. Then I addressed the weasel thus, �I�m afraid that I have to disagree with you about my father. You see, I believe that he is a frightful bore.�

Betty stifled another giggle and flashed her eyes at me. She always had such confoundedly beautiful eyes. It took a full minute for the weasel to work this one out and realise to whom he was speaking, during which time I took advantage of his confusion to offer Betty a cigarette and gallantly light it for her. Then he stepped back, horror-struck and dragged his wife away. It was another year or more before I saw her again but I recognised her instantly.

I was in town, Regent�s Park I believe. I was there on business, delivering papers for the society � one cannot trust the postal service � and had ventured out to take some air. She was pushing a monstrous perambulator and looking lost. �Excuse me, Miss,� I said, and she rushed on startled. I easily jogged to her side and she stood, defeated. �I am not planning to accost you, my dear,� I said. �You seemed lost and alone, that is all.�

�It is Nana�s day off,� she said in a whisper so low I had to drop my head to hear. �I was looking for the ducks. Deirdre does enjoy them so.�

She gestured to the baby with barely a glance at it and I leaned forward politely. I remember thinking what an ugly baby it was, with rather too much of the weasel about it.

I began to point her in the direction of the lake and then resolved to walk there with her myself. �We met last year,� I said as we headed towards it. �You came to the Hall, do you remember? I thought that my father was a frightful bore and I believe you thought so to.�

She smiled and covered her mouth with a gloved hand. �I remember,� she said. �George was so furious he�d made an ass of himself.�

She lowered her head so the brow of her hat hid her eyes. I decided she was the most exquisite creature I had ever seen. We arrived at the lake and parked the baby in full view of the ducks and other children. I asked her where she was staying in town, whether they kept a house here. She was awfully vague about everything so I decided not to push it. I asked her solicitously if she would require an ice-cream. She put her hand to her mouth again and gave the impression of coughing. I realised after a time that she was actually crying. �My dear!� I exclaimed. I made an awkward attempt to comfort her but she shrugged me off.

�Why are you so kind to me?� she asked at last, her words muffled by a handkerchief.

�Why should I not be?� I replied, quite aghast.

�You are a perfect stranger and yet you are more considerate than my own husband,� she said, this time with rather more composure.

�Well, then he is a brute,� said I, �and there�s nothing to be done about that. Many men are brutish as they feel they have the right to be.�

Presently the baby began to whimper and Betty became increasingly discomfited. I asked if we could meet again and again she was vague, but I did manage to extract an admission from her that she had enjoyed our time together. I walked her to the park entrance and then continued on to the office with a song in my heart.

I remember the feel of the hot paving beneath my feet and the smell in the air of a storm on the way. I remember thinking that I couldn�t care a jot if the heavens opened and hellfire rained down on me because I had met my life�s love. Oh, I�d had plenty of affairs and rendezvous already in my young existence but this was different. Those eyes, those full lips, that flawless luminosity. I had been struck by Cupid�s arrow and vowed that I would do all it took to possess her.

The next time we met was in a little teashop. She came right up to me and spoke.

�Miss Harding.�

I think I must have fallen into a doze, here in the corner of my mother�s sitting room. Just for a second then, I thought I heard Betty�s voice.

�Miss Harding? Are you Miss Harding?�

I sit bolt upright and squint at my ethereal visitor, a young woman with startlingly beautiful eyes and a familiar half-smile. �My darling B!� I cry. �You came back to me.� Then my joy is overtaken by the horror of what this phantom visitation can only mean � that I am soon to meet my own doom. I think I am about to have apoplexy and I actually begin to shriek.

�Oh Miss Harding, I�m so sorry. I didn�t mean to startle you, only at the desk they said�� Her words run on but I am not listening. Instead I am gawking at her clothes, her hair, her boots. I interrupt her.

�Betty my love, what have you done to yourself?�

�My name isn�t Betty,� she says. �May I take a seat?�

As I replace my specs, she explains at length that she is in fact Betty�s great-granddaughter, whose name it appears is Skye. She has been researching her family background since discovering certain facts about her great-grandmother and has come here, to the Hall, looking for the descendants of the woman with whom Betty ran off � i.e. me. The staff have informed her that I am a resident and so, with some trepidation it seems, she has approached me.

Skye is a student of journalism and carries a smart little Dictaphone machine with her everywhere. She cordially asks me if I would object to her recording our conversation and I obligingly remove my feet from the stool in order for her to place the item between us. I am initially a little sheepish following my outburst but soon recover my usual aloofness.

�So, my dear,� I begin, with an eye on the machine, �what is it that you�d like to know?�

�Everything really,� she says, rather unhelpfully, but then elaborates. �What my great-grandmother was like; what happened back then when you had your affair��

�We were together for seventy years. Slightly more than an affair, I feel,� I reply, somewhat haughtily.

�I�m sorry, I hadn�t realised. I didn�t mean to dismiss it. It�s just�well, I�ve only recently found out about all this and it was a bit of a skeleton in the closet, you know. I, er�well I should tell you that I�m a lesbian myself and I�ve just come out to my mother which is how the whole thing came to light.�

�Well, now that is interesting, isn�t it?� I peer at her a bit harder. I had initially thought that she was after the money. Perhaps she isn�t as mercenary as that after all. �Things like this do make one wonder about genetics, don�t you think?�

�They always warned me about �bad women� when I was a child and I never understood what they were getting at. When I came out my mother just said, �I knew it!� and I insisted that they explain. They didn�t want to tell me anything and only referred to it as an affair. I had assumed it was short-lived.�

�Of course, it was such a scandal for your family, especially for George. I wouldn�t put it past them to have told the little girl that her mother was dead.�

�Do you mean my grandmother?� Skye leans forward and pushes the recorder nearer to me.

�Deirdre was her name, I recall. A hideous little thing, poor dear. Far too much of her father in her, to my mind.� I lean back in the chair and she pushes the damnable machine a little nearer still.

�Did you meet her? My grandmother, I mean. Deirdre.�

�Only the once, when she was a baby.� I recall the events in the park and continue to outline Betty and our emerging friendship � the clandestine hotel rooms, how I dressed as a soldier, our weekend in Bath.

�And during all this time you never saw the baby?� asks Skye, voice high with incredulity.

�Well, of course I never went to their house. George had taken an instant dislike to me from day one. And B would not have brought the baby with her. Why would she? She had a nanny.�

�I don�t know, I just thought that maybe she�d be at home looking after the baby herself.�

I laugh. �There you are seeing the situation with your twenty-first century eyes. Women didn�t do that sort of thing in those days.�

Skye mutters quietly, �I�m sure the poorer women did.�

�Ah, now there is an assumption,� I say. �Two assumptions in fact. Number one: I am not deaf and you will kindly remember this when you presume that I will not hear your words. Number two: the impoverished women did not have the luxury to stay at home looking after their babies. Romantic visions of the homely farmwife did not exist outside novels. They had to work, so they would leave the babies with someone else � an aunt or older sibling � or leave the children to fend for themselves. This modern notion of the woman slaving at home in isolation as a drudge to her children is utter claptrap, invented by post-war male pride. It�s a travesty, a downright travesty, I say.�

There is a pause, then the machine declares with a loud click that it has completed its recording. Skye continues to look at me wordlessly and I gesture towards the thing. �I�m sorry, I should not have gone off like that. It seems that your machine needs some attention.�

�Oh, yes,� she says and busies herself with rearranging the cassette inside. As she does so, one of the staff approaches and announces that it is time for luncheon.

�My word, already!� I say. �Have I really been blathering for so long? But I must admit that I am rather hungry now. Could you possibly bring me a plate of roast beef sandwiches and something for my guest?�

�Oh I wouldn�t impose,� says Skye, startled. The uniformed girl hovers uncertainly.

�Nonsense my dear.� I lean forward and pat her hand. �And some cake,� I add. The girl nods and begins to walk away.

�I�m vegetarian!� Skye calls after her.

�We could do you an egg sandwich?� says the girl.

�Thank you,� replies Skye and she turns to me again. �Thank you very much. I must say they are very accommodating here. I didn�t expect�I mean, I�ve heard so many bad things about these kinds of places.�

�There is good and bad to everything, I believe. One should not presume to knowledge before experience. I am sure that there are terrible stories of these situations but mine is not one of them. Your great-grandmother was never here. She wanted to die before it came to this.� She winces; perhaps she is not accustomed to a person who is so frank about death. �You knew, of course, that Betty was dead?�

She nods. �My mother couldn�t tell me but I found out through the records office.�

�It comes to us all, my dear. Some sooner than others.�

�How did she die?� she asks.

�Happily,� I say. �In her own bed.� Because that, after all, was what she wanted most.

�I�m sorry, I didn�t mean to upset you.�

�That is quite all right, my dear,� I say, reaching for my handkerchief.

Skye concentrates again on the Dictaphone and, after a moment, replaces it on the footstool. �Tell me about your life together,� she says eagerly.

And so I begin with that dreadful time when George discarded her and forbade her from contact with the child. How devastated she was but how little we could do. I go on to our travel in Europe and our return on the eve of war. At this point our sandwiches arrive and I explain the impact of rationing. I urge Skye to take another slice of cake; honestly, these young people � so thin! The cassette is replenished again and I discuss our post-war optimism, the beautiful sixties, travel in America, my father�s death and my inheritance. Finally, how we settled in Kent and Betty discovering a propensity for gardening.

�Over the years,� I say, �B had a dream that one day her daughter would find her. It was not to be of course and I think that she knew this in her heart. But she always held out a hope. She would honour the child�s birthday every year with bittersweet celebration.�

�Oh, that�s so sad,� says Skye. �I wish I�d found you earlier. Maybe I��

�We should not dwell on what might have been but on what might be,� I say. �Come and visit me again. I shall find some photographs for you.�

�Yes, that would be lovely.�

�Lovely indeed,� I say. �And now you will excuse me. I feel so tired lately. I usually take a nap after lunch.�

�Of course,� she says and packs up her little machine and takes her leave.

After she has gone my mind whirls. So many reminiscences crowded into a small portion of the day is exhausting. I sleep fitfully, dreaming of incongruous situations: an elderly Betty pushing the fat perambulator; a young Betty in her greenhouse, watering the begonias. I dream that I am walking again through the corridors of this building at the height of a party. Yet the guests are people who never came here: women from America, women from Europe, women who over the years I have admired, with B always waiting just around the corner to discover us together. She never did, but I believe that she was ever aware of my flirtations and loved me still. My darling girl, my one true love. No one could supplant you.

I wake to the tinkle of the tea trolley. The four o�clock ritual. I take a cup of Earl Grey followed by another visit to the lavatory. Betty would take Earl Grey often until she realised she was becoming addicted to the bergamot. I sit looking out over the lawn. The cat sprawls on the grass enjoying the sun. He turns his head upside down and stares back at me unblinking. At last he gets up and stretches, then moves on; his nap is over.

We humans live such artificial lives. Our routines work against the natural rhythms of our bodies. I truly believe we should live more like cats. Napping, hunting, playing, eating. Doing all as it comes to one, without a plan, without palaver. Live life for today, I say, for who knows what tomorrow may bring. Each day I am alive is more remarkable than the last, if only for the mere fact that I am still alive after ninety-five years.

During my philosophising, the duffers return and begin their yawping. I am heartily sick of this. I retreat, broken at last. I meander through the corridors for a time, searching for a member of staff. The Hall has become deserted without a single soul in sight. I almost expect to slip back into my dream-world and to encounter some filly from my past. Finally, I practically trip over the little Asian girl who served my morning coffee. �I say,� I call as she scurries past. �I rather think that I might bathe before dinner. Do you suppose that you could find someone to assist?�

She nods and hurries away again. I am not sure whether she means to see to me herself or whether I should await her return. After dithering for a moment I head for the lift. This battered, cranky old contraption that has certainly seen better days reminds me strangely of myself. It creaks and groans as we are on our way up again. I wearily plod to room number ten and open the door.

I am surprised to find two girls already in there, running my bath and arranging towels. The Asian girl and another one with beefy arms. Their efficiency astonishes me. �Here we are, Miss Harding,� says the beefy-armed one. �Would you like some bubbles?�

�No thank you, my dear,� I say. �Just a dash of oil. And please make the water hot.� I undress and they help me to sit in the chair, towels draped over me unnecessarily. One of them pumps the handle while the other holds the chair steady and the whole apparatus rises with a screech of complaint. I am dizzy and about to hit the ceiling when they inform me that I should lift my legs, which I do, and then I am swung around over the bath. They remove the towels and lower me thankfully into the water. It is not as hot as I like it.

�Now, is there anything more you need?� says the beefy-armed one as she hands me my soap and flannel. I shake my head and they beat a path to the door. �We�ll be right out here,� she says. I am glad of the privacy and at least they shut the bathroom door so I am not forced to listen to their conversation. I begin to sluice myself down. After a moment I smell the distinctive whiff of cigarettes and I believe they are indulging in a sneaky smoke by my window. The audacity of these people! Still, I would prefer that rather than having them snooping through my possessions.

The aroma of tobacco draws me still, even after all this time. It must be forty years since my last smoke. It was never truly a habit for me but I did enjoy the occasional cigar or cigarillo. I even had a pipe for a time. B put paid to that though by complaining over the reek of it and I was banished to the shed.

I slosh around in the warm water. It is never as hot as I want, although I always ask. B used to call me a lobster when I bathed. She could easily use the same water after I�d had a good soak and still put more cold into the tub.

Voices approach and there is a gentle knock at the door. �Are you done?� they call.

�Yes,� I say resignedly. �Yes, I am quite done, thank you.�

Then there is the bustle. The unplugging of the bath, the uplifting of the chair, the draping of the towels. Finally I am standing and being robustly rubbed down by both girls, then I take my dressing-gown over my shoulders and shuffle into my room to dress. I select a clean pair of trousers and a blouse and dismiss the girls� offers of help. Presently, I take my spectacles from the dresser, then brush my hair.

I am tempted to stay in my room for the evening as I am not sure I could face the battle for the lounge chair again. It seems such a waste of time; everything seems a waste of time. And yet how else would I expend my time? I no longer read as my eyesight is so poor, even with the specs; the radio bores one after a while; nothing could compel me to join the residents in the television lounge. My day consists of the stark routine of the institution seasoned by my memories.

As with one�s life, the early part of the day drags on so and the evening speeds by with alarmingly swift velocity. I shall be tardy if I do not head down soon so I square my shoulders and brave the elevator once more.

Down in the lobby, the rabble are assembling for dinner. We generally dine at seven so they are rather early. I notice one of the senior staff at the piano and am wondering if we are scheduled for a music evening when a cry goes up. �She�s here!� A rousing chorus of �Happy Birthday� begins. I stand speechless and overwhelmed as I realise they are singing for me.

I remove my specs and allow them to dangle on the cord. I blink back tears; it would not do to permit them to see me cry. To my amazement a cake is presented, with a large central candle. They jovially ask me to blow it out. �Really, there is no need for such fuss,� I begin but soon I am caught up in the celebration and I even consent to a small slice of cake myself.

The evening meal passes in rather a blur, which may be to do with the glass of sherry that I am offered. I believe I have eaten some sort of pie. When I retire to the lounge, I am pleased to find my seat vacant. I sit and watch the evening golden sunlight drench the patch of lawn in front of the French windows. The day dwindles. The cat has withdrawn, no doubt to find a female feline somewhere and spend the evening in romantic caterwauling.

I squander the remains of the daylight in quiet contemplation. I find that I am ever surprised by folk and their ways. Every day among the ordinary there is something extraordinary to astonish one. The night-time tea trolley clatters by to service those few who linger downstairs. I take a milky hot chocolate, reminding me again of Betty and her proclivities.

My dearest darling, I miss you so. Words cannot express. You were everlastingly the mainstay of my life. Seventy years together, almost to the day. I was twenty-three and you were twenty; so young, so full of verve. I loved you to death.

By rights I should have been the one to die first, not her. But I do not feel cheated. The places we visited, the times we had, return to me now as a gift. My memories blur occasionally but in the main they arrive with clarity. The most enduring memory is our last day together, perhaps because it was planned so meticulously.

It was not long after the tumour had been discovered. The doctor explained the various therapies but Betty would have none of it. I tried to persuade her but she was not one to be swayed. Once she made her mind up to do something there was no stopping her. I used to say to her, �Leave the dishes until the morning,� and she would always reply, �If I am going to do something then I should like to do it when and how I choose.�

We had always agreed that there would be no lingering, no last desperate holding on to sullied flesh. She spent some time putting her affairs in order, demonstrating to me the care of the garden, coordinating plans for her funeral, visiting a few special places until she was too weak to travel anymore. The last will and testament was made out to various charities, there being no family and no need for me to inherit her money. Then we had a few days at home.

We had prepared stocks of insulin, Betty having been diabetic for a while, and a good supply of alcohol and groceries. The menu was set for the day and we had someone in to prepare the food as if it were a dinner party. Betty spent the morning in her garden. We brought in cut flowers and filled the house with their scent. It was spring and we had lupins. We said goodbye to each other in style and took to our bed without upset. She was not frightened but philosophical. I believe that I was more fearful than B, for I was the one to be left behind.

I did not sleep that night. I stayed beside her as she slipped into her last and longest sleep, holding her close and silently weeping. The hours of darkness crept by so slowly that I began to believe the day would never dawn, that all life had been snuffed out with B. Then as if a miracle occurred, the sun�s pale fingers began to sidle into the room until gradually the light became brighter and more intense.

As unreal a situation as this I had never experienced. I could not grasp the fact that she was gone when her body lay warm beside me. That the day was dawning somehow seemed unfair. Given my feeling that the dawn would not come, I now came to believe that B would arise with the sun. Although I knew her to be dead I began to shake her body expecting her to awaken, miraculously cured.

I suppose I may have slipped into a kind of madness for a time. Our carefully laid plan of me calling the doctor and explaining how I had discovered her flew out of the window. Instead I dialled 999 and shrieked into the telephone at the operator. When the ambulance arrived I had gathered some of my composure and thankfully did not require sedation.

The days following this are a shadow. The funeral went as arranged: a video had been made of our photograph albums and B�s favourite musical compositions were played. Over that summer I was visited by representatives of various authorities who offered their services, all of whom were dismissed with short shrift. I adopted a neighbour�s cat for a few weeks when they were abroad; I took long walks; I sat and cried over Betty�s dying garden. This was not my finest hour but soon enough I established a routine for myself. Gradually I could make it through the day without being assaulted from all sides by distressing emotion. I find that I still remember her in every little thing but it no longer hurts quite so much.

As I sit in my mother�s corner, I feel that my life has come full circle. I am ready to follow my darling. I will wait a while longer. Presently, I go up the wooden hill to Bedfordshire, as B would say. The elevator behaves itself with only a minor rattle to send me on my way.

Here I am yet again at number ten. I slowly exchange my eveningwear for a long nightdress and make myself comfortable with a blanket and cushions arranged in my chair. I say farewell to the sun for another day. It has already disappeared behind the house, the last rays creating long shadows over the grounds. I thank all the gods that exist for another day safely travelled. If I die tonight, like Shakespeare, on my birthday, I will die fulfilled. If I wake tomorrow, I will thank them for another miracle.

My last thought of the day is Betty, as always. As I slide towards slumber, I remember her final words, �I�ll see you on the other side�.

TERRY PRATCHETT

TERRY PRATCHETT  FAY WELDON

FAY WELDON  SALMAN RUSHDIE

SALMAN RUSHDIE  JOANNE HARRIS

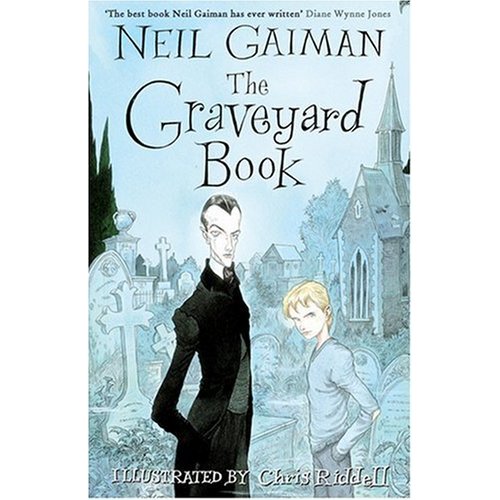

JOANNE HARRIS  NEIL GAIMAN

NEIL GAIMAN