THE CHILD

by

Ali Smith

I went to Waitrose as usual in my lunchbreak to get the weekly stuff. I

left my trolley by the vegetables and went to find bouquet garni for the

soup. But when I came back to the vegetables again I couldn�t find my

trolley. It seemed to have been moved. In its place was someone else�s

shopping trolley, with a child sitting in its little child seat, its fat

little legs through the leg-places.

Then I glanced into the trolley in which the child was sitting and

saw in there the few things I�d already picked up: the three bags of

oranges, the apricots, the organic apples, the folded copy of The Guardian

and the tub of kalamata olives. They were definitely my things. It was

definitely my trolley.

The child in it was blond and curly-haired, very fair-skinned and

flushed, big-cheeked like a cupid or a chub-fingered angel on a Christmas

card, a child out of an old-fashioned English children�s book, the kind of

book where they wear sunhats to stop them getting sunstroke all the post-war

summer. This child was wearing a little blue tracksuit with a hood and blue

shoes, and was quite clean, though a little crusty around the nose. Its

lips were very pink and perfectly bow-shaped; its eyes were blue and clear

and blank. It was an almost embarrassingly beautiful child.

Hello, I said. Where�s your mother?

The child looked at me blankly.

I stood next to the potatoes and waited for a while. There were

people shopping all round. One of them had clearly placed this child in my

trolley and when he or she came to push the trolley away I could explain

these were my things and we could swap trolleys or whatever and laugh about it and I could get on with my shopping as usual.

I stood for five minutes or so. After five minutes I wheeled the

child in the trolley to the Customer Services desk.

I think someone somewhere may be looking for this, I said to the

woman behind the desk, who was busy on a computer.

Looking for what, Madam? she said.

I presume you�ve had someone losing their mind over losing him, I

said. I think it�s a him. Blue for a boy, etc.

The Customer Services woman was called Marilyn Monroe. It said so on

her namebadge.

Quite a name, I said, pointing to the badge.

I�m sorry? she said.

Your name, I said. You know. Monroe. Marilyn.

Yes, she said. That�s my name.

She looked at me like I was saying something dangerously

foreign-sounding to her.

How exactly can I help you? she said in a singsong voice.

Well, as I say, this child, I said.

What a lovely boy! she said. He�s very like his mum.

Well, I wouldn�t know, I said. He�s not mine.

Oh, she said. She looked offended. But he�s so like you. Aren�t

you? Aren�t you, darling? Aren�t you, sweetheart?

She waved the curly red wire attached to her keyring at the child,

who watched it swing inches away from his face, nonplussed. I couldn�t

imagine what she meant. The child looked nothing like me at all.

No, I said. I went round the corner to get something and when I got

back to my trolley he was there, in it.

Oh, she said. She looked very surprised. We�ve had no reports of a

missing child, she said.

She pressed some buttons on an intercom thing.

Hello? she said. It�s Marilyn on Customers. Good thanks, how are

you? Anything up there on a missing child? No? Nothing on a child?

Missing, or lost? Lady here claims she�s found one.

She put the intercom down. No Madam, I�m afraid nobody�s reported

any child that�s lost or missing, she said.

A small crowd had gathered behind us. He�s adorable, one woman said.

Is he your first?

He�s not mine, I said.

How old is he? another said.

I don�t know, I said.

You don�t? she said. She looked shocked.

Aw, he�s lovely, an old man, who seemed rather too poor a person to

be shopping in Waitrose, said.

He got a fifty pence piece out of his pocket, held it up to me and

said : Here you are. A piece of silver for good luck.

He tucked it into the child�s shoe.

I wouldn�t do that, Marilyn Monroe said. He�ll get it out of there

and swallow it and choke on it.

He�ll never get it out of there, the old man said. Will you? You�re

a lovely boy. He�s a lovely boy, he is. What�s your name? What�s his

name? I bet you�re like your dad. Is he like his dad, is he?

I�ve no idea, I said.

No idea! the old man said. Such a lovely boy! What a thing for his

mum to say!

No, I said. Really. He�s nothing to do with me, he�s not mine. I

just found him, in my trolley, when I came back with the -

At this point the child sitting in the trolley looked at me, raised

his little fat arms in the air at me and said, straight at me : Mammuum.

Everybody round me in the little circle of baby admirers looked at

me. Some of them looked knowing and sly. One or two nodded at each other.

The child did it again. It reached its arms, almost as if to pull

itself up out of the trolley seat and lunge straight at me through the air.

Mummaam, it said.

The woman called Marilyn Monroe picked up her intercom again and

spoke into it. Meanwhile the child had started to cry. It screamed and

bawled. It shouted its word for mother at me over and over again and shook

the trolley with its shouting.

Give him your car keys, a lady said. They love to play with car

keys.

Bewildered, I gave the child my keys. It threw them to the ground

and screamed all the more.

Lift him out, a woman in a Chanel suit said. He just wants a little

cuddle.

It�s not my child, I explained again. I�ve never seen it before in

my life.

Here, she said.

She had pulled the child out of the wire basket of the trolley seat,

holding it at arm�s length so her little suit wouldn�t get smeared. It

screamed even more as its legs came out of the wire seat, its face got

redder and redder and the whole shop resounded with the screaming. (I was

embarrassed. I felt peculiarly responsible. I�m so sorry, I said to the

people round me.) The Chanel woman shoved the child hard into my arms.

Immediately it put its arms round me and quietened to fretful cooing.

Jesus Christ, I said, because I had never felt so powerful in all my

life.

The crowd round us made knowing noises. See? a woman said. I

nodded. There, the old man said. That�ll always do it. You don�t need to

be scared, love.

Such a pretty child, a passing woman said. The first three years are a

nightmare, another said, wheeling her trolley past me towards the fine

wines. Yes, Marilyn Monroe was saying into the intercom. Claiming it

wasn�t. Hers. But I think it�s all right now. Isn�t it Madam? All right

now? Madam?

Yes, I said through a mouthful of the child�s blond hair.

Go on home, love, the old man said. Give him his supper and he�ll be

right as rain.

Teething, a woman ten years younger than me said. She shook her

head; she was a veteran. It can drive you crazy, she said, but it�s not

forever. Don�t worry. Go home now and have a nice cup of herb tea and

it�ll all settle down, he�ll be asleep as soon as you know it.

Yes, I said. Thanks very much. What a day.

A couple of women gave me encouraging smiles, one patted me on the

arm. The old man patted me on the back, squeezed the child�s foot inside

its shoe. Fifty pence, he said. That used to be ten shillings. Long

before your time, little soldier. Used to buy a week�s worth of food, ten

shillings did. In the old days, eh? Ah well, some things change and some

others never do. Eh? Eh Mum?

Yes. Ha ha. Don�t I know it, I said, shaking my head.

***

I carried the child out into the carpark. It weighed a ton.

I thought about leaving it right there in the carpark behind the

recycling bins, where it couldn�t do too much damage to itself and someone

would easily find it before it starved or anything. But I knew that if I

did this the people in the store would remember me and track me down after

all the fuss we�d just had. So I laid it on the back seat of the car,

buckled it in with one of the seatbelts and the blanket off the back window,

and got in the front. I started the engine.

I would drive it out of town to one of the villages, I decided, and

leave it there, on a doorstep or outside a shop or something, when no-one

was looking, where someone else would report it found and its real parents

or whoever had lost it would be able to claim it back. I would have to

leave it somewhere without being seen, though, so no one would think I was

abandoning it.

Or I could simply take it straight to the police. But then I would

be further implicated. Maybe the police would think I had stolen the child,

especially now that I had left the supermarket openly carrying it as if it

were mine after all.

I looked at my watch. I was already late for work.

I cruised out past the garden centre and towards the motorway and

decided I�d turn left at the first signpost and deposit it in the first

quiet, safe, vaguely-peopled place I found, then race back into town. I

stayed in the inside lane and watched for village signs.

You�re a really rubbish driver, a voice said from the back of the

car. I could do better than that, and I can�t even drive. Are you for

instance representative of all women drivers, or is it just you among all

women who�s so rubbish at driving?

It was the child speaking. But it spoke with so surprisingly

charming a little voice that it made me want to laugh, a voice as young and

clear as a series of ringing bells arranged into a pretty melody. It said

the complicated words, representative and for instance, with an innocence

that sounded ancient, centuries old, and at the same time as if it had only

just discovered their meaning and was trying out their usage and I was

privileged to be present when it did.

I slewed the car over to the side of the motorway, switched the

engine off and leaned over the front seat into the back. The child still

lay there helpless, rolled up in the tartan blanket, held in place by it

inside the seatbelt. it didn�t look old enough to be able to speak. It

looked barely a year old.

It�s terrible. Asylum seekers come here and take all our jobs and

all our benefits, it said preternaturally, sweetly. They should all be sent

back to where they come from.

There was a slight endearing lisp on the s sounds in the words asylum

and seekers and jobs and benefits and sent.

What? I said.

Can�t you hear? Cloth in your ears? it said. The real terrorists

are people who aren�t properly English. They will sneak into football

stadiums and blow up innocent Christian people supporting innocent English

teams.

The words slipped out of its ruby-red mouth. I could just see the

glint of its little coming teeth.

It said : The pound is our rightful heritage. We deserve our

heritage. Women shouldn�t work if they�re going to have babies. Women

shouldn�t work at all. It�s not the natural order of things. And as for

gay weddings. Don�t make me laugh.

Then it laughed, blondly, beautifully, as if only for me. Its big

blue eyes were open and looking straight up at me as if I were the most

delightful thing it had ever seen.

I was enchanted. I laughed back.

From nowhere a black cloud crossed the sun over its face, it screwed

up its eyes and kicked its legs, waved its one free arm around outside the

blanket, its hand clenched in a tiny fist, and began to bawl and wail.

It�s hungry, I thought, and my hand went down to my shirt and before

I knew what I was doing I was unbuttoning it, getting myself out, and

planning how to ensure the child�s later enrolment in one of the area�s

better secondary schools.

***

I turned the car around and headed for home. I had decided to keep the

beautiful child. I would feed it. I would love it. The neighbours would

be amazed that I had hidden a pregnancy from them so well, and everyone

would agree that the child was the most beautiful child ever to grace our

street. My father would dandle the child on his knee. About time too, he�d

say. I thought you were never going to make me a grandfather. Now I can

die happy.

The beautiful child�s melodious voice, in its pure RP pronunciation,

the pronunciation of a child who�s already been to an excellent public

school and learned how exactly to speak, broke in on my dream.

Why do women wear white on their wedding day? it asked from the back

of the car.

What do you mean? I said.

Why do women wear white on their wedding day? it said again.

Because white signifies purity, I said. because it signifies -

To match the stove and the fridge when they get home, the child

interrupted. An Englishman, an Irishman, a Chineseman and a Jew are all in

an aeroplane flying over the Atlantic.

What? I said.

What�s the difference between a pussy and a cunt? the child said in

its innocent pealing voice.

Language! please! I said.

I bought my mother-in-law a chair, but she refused to plug it in, the

child said. I wouldn�t say my mother-in-law is fat, but we had to stop

buying her Malcolm X t-shirts because helicopters kept trying to land on

her.

I hadn�t heard a fat mother-in-law joke for more than twenty years.

I laughed. I couldn�t not.

Why did they send premenstrual women into the desert to fight the

Iraqis? Because they can retain water for four days. What do you call a

Pakistani with a paper bag over his head?

Right, I said. That�s it. That�s as far as I go.

I braked the car and stopped dead on the inside lane. Cars squealed

and roared past us with their drivers leaning on their horns and shaking

their fists. I switched on the hazard lights. The child sighed.

You�re so politically correct, it said behind me, charmingly. And a

terrible driver. How do you make a woman blind? Put a windscreen in front

of her.

Ha ha, I said. That�s an old one.

I took the B roads and drove to the middle of a dense wood. I opened

the back door of the car and bundled the beautiful blond child out. I

locked the car. I carried the child for half a mile or so until I found a

sheltered spot, where I left it in the tartan blanket under the trees.

I�ve been here before, you know, the child told me. S�not my first

time.

Goodbye, I said. I hope wild animals find you and raise you well.

I drove home.

But all that night I couldn�t stop thinking about the helpless child

in the woods, in the cold, with nothing to eat and nobody knowing it was

there.

I got up at 4am and wandered round my bedroom. Sick with worry, I drove

back out to the wood road, stopped the car in exactly the same place and

walked the half-mile back into the trees.

There was the child, still there, still wrapped in the tartan travel

rug.

You took your time, it said. I�m fine, thanks for asking. I knew

you�d be back. You can�t resist me.

I put it in the back seat of the car again.

Here we go again. Where to now? the child said.

Guess, I said.

Can we go somewhere with broadband so I can look up some internet

porn? the beautiful child said, beautifully.

I drove to the next city and pulled into the first supermarket

carpark I passed. It was 6.45 am and it was open.

Ooh, the child said. My first 24 Hour Tesco�s. I�ve had an Asda and

a Sainsbury�s but I�ve not been to a Tesco�s before.

I pulled the brim of my hat down over my eyes to evade being

identifiable on closed circuit and carried the tartan bundle in through the

out doors when two other people were leaving. The supermarket was very

quiet, but there were one or two people shopping. I found a trolley,

half-full of good things, French butter, Italian olive oil, a folded new

copy of The Guardian, left standing in the biscuits aisle, and emptied the

child into it out of the blanket, slipped his pretty little legs in through

the gaps in the opened child seat.

There you go, I said. Good luck. All the best. I hope you get what

you need.

I know what you need all right, the child whispered after me, but

quietly, in case anybody should hear. Psst, he hissed. What do you call a

woman with two brain cells? Pregnant! Why were shopping trolleys invented?

To teach women to walk on their hind legs!

Then he laughed his charming peal of a pure childish laugh and I

slipped away out of the aisle and out of the doors past the shopgirls

cutting open the plastic binding on the morning�s new tabloids and arranging

them on the newspaper shelves, and out of the supermarket, back to my car,

and out of the carpark, while all over England the bells rang out in the

morning churches and the British birdsong welcomed the new day, God in his

heaven, and all being right with the world.

� Ali Smith

Reproduced with permission

This story was originally published in Blithe House Quarterly

THE CIRCUS, dir. Charles Chaplin

THE CIRCUS, dir. Charles Chaplin DOGVILLE, dir. Lars von Trier

DOGVILLE, dir. Lars von Trier MADCHEN IN UNIFORM, dir. Leontine Sagan

MADCHEN IN UNIFORM, dir. Leontine Sagan OLIVER, dir. Carol Reed

OLIVER, dir. Carol Reed THE ACCIDENTAL

THE ACCIDENTAL THE WHOLE STORY AND OTHER STORIES

THE WHOLE STORY AND OTHER STORIES HOTEL WORLD

HOTEL WORLD OTHER STORIES AND OTHER STORIES

OTHER STORIES AND OTHER STORIES LIKE

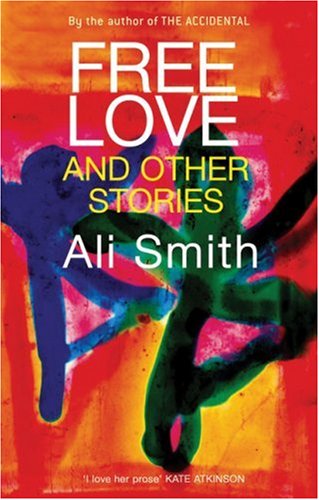

LIKE FREE LOVE

FREE LOVE